A few years back, I found myself in a large Telco navigating what was touted as an “agile” transformation. The premise was straightforward: decouple the management of work from the management of people. Delivery leads would oversee the day-to-day tasks, while “people managers” would focus on performance reviews, coaching, and professional development. The idea was that individuals would “flow to work,” being allocated to projects that matched their skills and aspirations, with their growth shepherded by someone not entangled in the immediate delivery pressures.

At first glance, it seemed like a progressive approach—flexible, empowering, and modern. But as the days turned into months, the cracks began to show. Let’s set aside, for a moment, the chaos created by shallow OKRs and incoherent prioritisation (leading to a whole bunch of partially supported projects instead of the critical ones fully supported). What became increasingly clear was something more structural: you can’t meaningfully separate the work someone does from the person doing it.

1. Accountability Gets Split (And Then Lost)

When the person guiding your work isn’t the one accountable for your performance, who actually owns the outcome?

- The delivery lead sees the day-to-day results and struggles.

- The people manager sits too far from the action to make a grounded judgement.

- Each thinks the other has the handle on what matters most.

In practice, accountability becomes a shared illusion. Everyone is sort of responsible. Until something goes wrong—and then no one really is.

What emerges is a vacuum. No one owns the full person-in-role system. And that’s where performance problems, disengagement, and unmet development needs tend to fester.

2. Development Without Context Isn’t Development

You can’t coach someone effectively if you’re not present in the conditions where they apply what they’ve learned.

- A people manager, disconnected from delivery, can’t see how context shapes behaviour or performance.

- A delivery lead, focused on outputs, might not be paying attention to longer-term growth, role fit, or learning loops.

The result? Feedback becomes generic. Coaching becomes abstract. And the person sits in the middle trying to reconcile two versions of what good looks like—one rooted in theory, the other in execution, neither aligned.

Growth doesn’t happen in the abstract. It happens in real work, under real constraints. Managing that requires context and continuity.

3. Role Stress Goes Up, Not Down

Instead of freeing people, dual structures often leave them navigating a tangle of split expectations.

- Conflicting priorities between “task” and “people” leads.

- Unclear authority when guidance contradicts.

- Emotional friction from trying to please both.

Over time, this creates exactly what Elliott Jaques described as role conflict. People spend more time managing the structure than doing the work.

The structure becomes noise. It erodes trust, blurs accountability, and increases cognitive load—all in the name of agility.

What Would Jaques Say?

Because I got the inspiration to write this from a post on LinkedIn questing if we needed hierarchy and I responded with some thoughts about Elliott Jaques’s work I wonder what he might have had to say. I imagine that he would offer a sharp and simple critique:

A role should have one manager.

That manager should be accountable for both the outputs of the role and the development of the person in it.

Not out of some love for command-and-control, but because coherent accountability enables clarity. And clarity enables real support. You can’t help someone grow if you don’t also see how they’re performing. And you can’t assess performance if you don’t understand the complexity of the role.

Noble Intentions, Flawed Design

To be fair, many of these structures come from good intentions:

- Reducing bottlenecks in traditional hierarchies.

- Sharing leadership across technical and people domains.

- Creating space for peer mentoring and distributed learning.

But without a structurally sound foundation, they tend to deliver:

- Diffuse authority

- Unclear decision rights

- Disempowered teams

- Stressful ambiguity

And in complex work, ambiguity in structure rarely leads to innovation. It leads to drift.

Better Ways to Do This

To create adaptive, coherent organizations without fragmenting accountability, unify work and people management within structures that empower self-organization and local decision-making:

- Single-Point Accountability with Subsidiarity: Assign one manager to oversee both role performance and personal development, ensuring clarity, context, and continuity. This manager holds full responsibility for the person-in-role system, drawing on specialists (e.g., technical coaches) for support without splitting authority. Empower local decision-making by granting authority to the lowest level with adequate information (subsidiarity), as local knowledge is critical for smart, timely adaptations in complex environments. Ensure local decisions align with global requirements—such as organizational goals, standards, or strategic priorities—through transparent communication and shared frameworks, maintaining coherence across the enterprise.

- Porous Boundaries and Transparency: Define roles with clear purposes and decision rights, but ensure boundaries between teams are permeable to enable rich information flow. Break down silos by fostering open communication across and through organizational layers, aligning with market demands and customer value. Transparency builds trust, allowing teams to self-organize around shared goals without competing internal priorities.

- Hybrid Roles for Requisite Variety: Equip technical leads to handle both delivery and development as hybrid “player-coaches,” supported by training to balance these responsibilities. This ensures managers have the contextual insight to coach effectively while maintaining accountability. Design roles to provide enough response variety to match the complexity of inputs, enabling teams to adapt dynamically to changing conditions.

- Incremental Change with Humility: Approach change incrementally, monitoring feedback to detect unintended consequences and adjust course. Manager must embrace humility, recognizing the limits of control in complex systems. Treat “resistance” as valuable information, not a threat, and foster a culture of continuous learning to refine solutions collaboratively.

- People-Centric Leadership for Self-Organization: Cultivate managers who trust in the workforce’s capacity to self-organize around meaningful work. Encourage employees to identify and solve issues that matter to them, as seen in successful bottom-up initiatives. Align efforts with a customer-centric purpose, ensuring all actions create value, and leverage informal networks to drive innovation and collaboration.

These principles create organizations that are adaptive yet coherent, empowering people to thrive within a unified framework that delivers value and fosters trust.

Final Thought

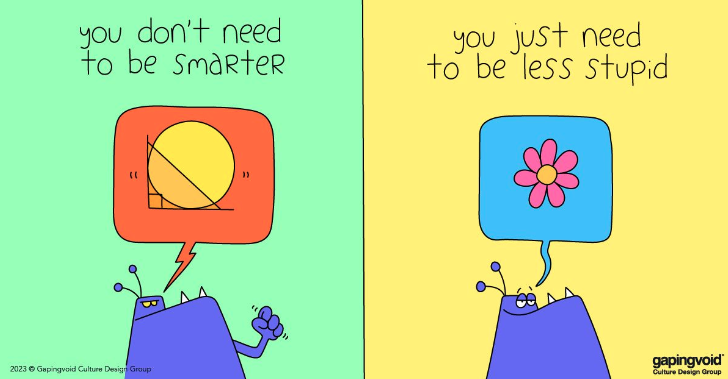

You can’t separate people from the work they do. Attempts to do so—however well-intentioned—often leave organisations with structural ambiguity, role confusion, and diminished trust.

Agile may call it flexibility. But in complex systems, clarity is what actually enables adaptability. And the best kind of structure isn’t the one with the fewest rules—it’s the one where the rules are clear, coherent, and help people do their best work.