understanding the work part 2

In my last post when I spoke about systems of work, I also made a point that many Managers don’t really understand the system of work that they are accountable for. In this post I want to dig a bit deeper into this topic.

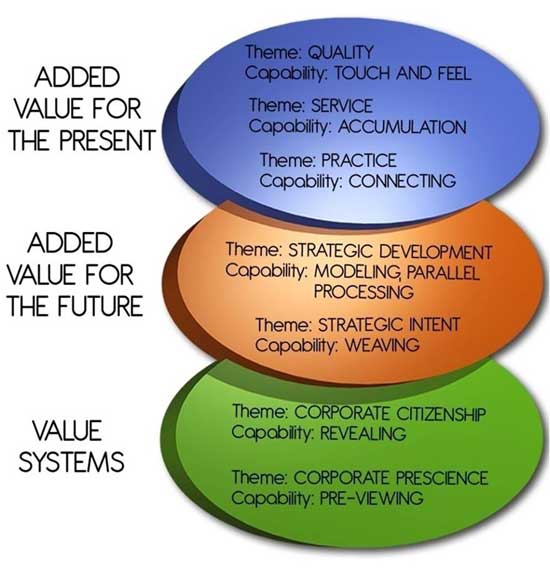

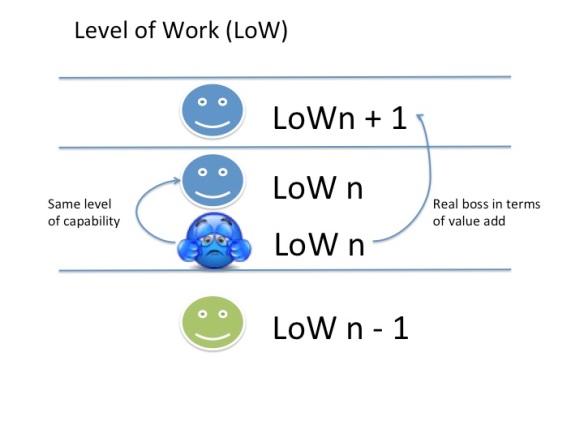

As you move vertically through the management structure of an organisation the work being done is different (or at least it should be). It is important to understand what is different about the work at different levels of management and that it is not just more of the same or more difficult work technically.

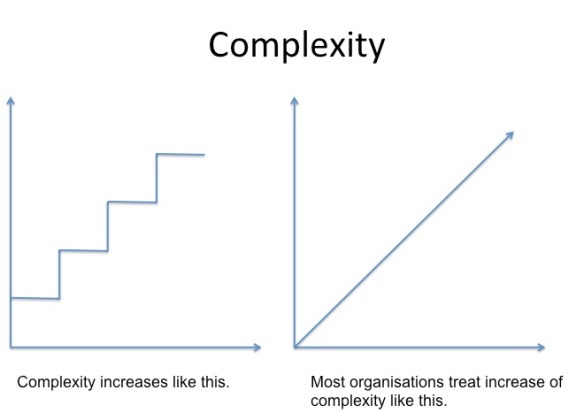

So what is it that is different, what do we look for to make this distinction? The answer is – (as it usually is…) it depends. It depends on the level of work, as it is both the focus of the work and the complexity of the work that should shift as you move vertically in the organisation. Gillian Stamp from BIOSS developed a helpful framework to distinguish the difference that makes a difference with respect to the work at different levels of management. The product of this thinking is the idea of Work Domains and it builds on Jaques’ idea of “levels of work” and I think presents it in a better way. Stamp and Elliot did work together for some time at BIOSS so no surprise that they share this view.

Three Tools of Leadership

Increasing complexity means you as a Manager need a broader set of tools to work with. At lower levels your own behaviour is your main tool to influence the team together with and understanding of team dynamics (i.e. team leadership). Understanding and being aware of how your interpersonal leadership style impacts performance and how your team work together is of course critical at all levels of leadership but a lower levels i.e. supervisor and/or first level team leader the authority and accountability for organisational systems are not there so as leader you can only influence these, not authorise changes to them.

There is a saying that I first came across when working with a global mining company many years ago that had a great impact on me. They used it in the context of safety issues but it is applicable in a broader context:

“The standard you walk past is the standard you accept.”

In other word, your actions or inaction as a leader when unproductive or undesirable behaviours occur within the team sets the tone for what is accepted.

However, as we move up through the hierarchy relying on your interpersonal skills alone is no longer sufficient because you will no longer be able to have a personal relationship with everyone in the organisation.

So what other tools might leaders in more senior positions require?

Systems Leadership suggests that there are three tools; systems, symbols, and behaviour, that successful managers understand and use.

So whilst, role modelling is critical for challenging unproductive behaviours, it is not enough for sustainable change. You also need to align the systems and symbols of the organisation. Having said that, if you as a leader cannot be bothered to actually live and behave in way that is consistent with what you want staff to do you might as well throw your change initiative in the bin straight away.

When I said earlier that many managers do not understand the system of work they work in or are accountable for this is exactly what I mean. There is lack of understanding of how the system is shaping and driving the behaviour of the people and overall performance. Without a theory for understanding this, changing it becomes a terribly difficult task.

The desire is of course for the authorised systems to be productive. Often they are either not as productive as they could be or they are productive despite of the manifest design. In other words the extant (or real) system is different from the official authorised system, usually became staff develop unauthorised “workarounds” to produce good customer outcomes.

For senior executives it is essential to understand how systems work so that they can design appropriate organisations systems to deliver on the purpose of the organisation. Designing the organisation is the role of senior management; a role that I often see being delegated way down in the HR function to someone with no real authority, often lack the capability to do this level of work, and often with no real understanding of organisational design theories or organisational systems.

A helpful theory for understanding the critical functions in an organisation and the relationships between them is Stafford Beer’s work in Management Cybernetics – The Viable System Model. In a previous post there is a video by Javier Livas explaining the Universal Management System, which is the VSM in less complex language. If you want to watch an in-depth video of the VSM by Javier, you can email him to request access details from his YouTube account. I thoroughly recommend doing so it you can find the time to view the full 2 hour video.

In short, the VSM views an organisation as a system that requires five key functions to remain viable (i.e. maintain its existence). The five systems are recursive (or nested in each other like a Russian doll) so every system one is in turn made up by the five key functions:

System 1 – Operations

System 2 – Coordination

System 3 – Management

System 3* – Audit & Monitoring

System 4 – Development

System 5 – Policy

I will not go on in detail about the VSM as many other better writers and thinkers have done a great job of this already, Beer alone wrote at many books on the topic: The Brain of the Firm, The Heart of Enterprise, Diagnosing the System of Organisation to name a few.

I have found the VSM to be an outstanding theory to work with when diagnosing organisations. It provides immense value and insights and I can discuss the insights with clients without getting into the underlying theory in too much detail. The beauty of the VSM in my view is the recursive nature of the model, which means it is applicable for systems at any levels and Managers across an organisation, can all get value from it. It does require some investment in time to get your head around but it is well worth the investment.

Another “theory” I am a big fan of is the Vanguard Method. Its use in service organisations and it has greatly influenced my thinking and my work. Like any method it is not all-encompassing and I have found the mix of The Vanguard Method, Systems Leadership and The Viable System Model to be very powerful and insightful across multiple levels of organisational complexity.

In a service organisation, one of the quickest ways to make value creating more difficult, is to functionalise the work. This is just one of the many issues that emerge when applying tools and ideas that were designed to solve manufacturing issues in a service or knowledge environment. Functionalization of work is based on the assumption that someone with specialist skills will perform a task faster and to a higher quality. Whilst this seems to make sense it fails to account for the flow of the work and is based on Tayloristic view of the workplace.

If you read up on articles or books by John Seddon you will find that he keeps banging on about the damage from the “economies of scale” mentality that permeates most organisations. His point is that they should shift to understanding demand and design the flow of work accordingly. Seddon is trying to shift ingrained mental models of how organisations operate many of which came about due to Taylor’s theory becoming the mainstream one and the ideas of others such as Mary Parker Follett, were less successful at the time. Only now after the failings of the mechanistic view of organisations are we starting to embrace her ideas employee engagement and power with rather than power over. This is not to say that Taylor’s ideas were useless, they did help the industrialisation of the world. We can only guess how different the world of work might have been if Follett’s more humanistic ideas had been the dominant ones.

In the spirit of economies of scale we tend to measure activity (because being busy and high utilisation of our time is important…seemingly regardless of what we are doing) instead of measuring how well we deliver on what matter to the customer, treat all demand the same. John Seddon made life a bit easier by coining the term “failure demand” as he gave word and enhanced meaning to something I had come across many times but just treated as COPQ (cost of poor quality or rework). Its significance as leverage for improvement quickly became evident through Seddon’s work. For me earliest time I can remember identifying this was at a when doing some work to understand the complaints process in a public housing organisation where we came across an unreasonable amount of plumbing issues in relation to the amount of properties owned by the organisation. The practice was to just log the complaints about poor work, no shows and rescheduled visits as new jobs. This hid away the true volume of value work amongst all of the failure demand – i.e. demand created by a failure of doing the right thing for the customer the first time or failing to do it at all.

What Vanguard does really well is providing a method “Check –Plan – Do” for understanding the flow of the primary activities (System 1 in VSM language) at the level of recursion where the customer interaction occurs. For me the gap with the Vanguard method relates to how to embed constructive leadership behaviours and models to support a new way of thinking (and subsequently a new way of working) such as the decision making model and the task assignment model I outlined in a previous post. At higher levels in the organisations the work is more focussed on how all the other systems across multiple recursions are meant to work together to support value creation for customers.

Usually the feedback systems are in terms of hard numbers such as “productivity measures” or process output measures. More often than not, they are looking at the wrong things and provide little if any understanding of the system of work. Activity measures are in place to measure performance with a complete disregard for the inherent variety in demand that comes in and failure demand is treated as value demand.

Understanding demand, understanding variation, understanding the connections and feedback loops in “your” level of recursion (as part of the VSM), understanding the systems, symbols and behaviours that reinforce or contradict the desired culture are all important aspects for Managers to consider when they grapple with the difficult task of “understanding the work”.

It is not easy, it is a complex task but with some good theories and models it becomes less challenging.