My most recent collaborator Dr Richard Claydon wrote another great post the other day on how art (in this case TV shows) reflects the fears of society. In his post, which I encourage you to read, not only because he is a good writer, but this post might make more sense if you do.

I recently heard a story of a former colleague’s exchange with a senior partner from a global consultancy. My colleague asked, in earnest, what underlying theories the company used to inform their practice. The partner looked perplexed by the question, so after some clarification the partner said; oh, we use international best practice.

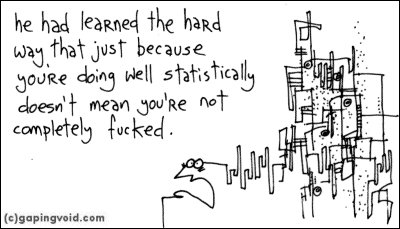

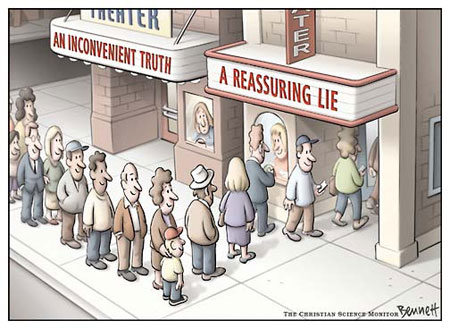

What on earth does that mean? You copy what others are doing without knowing why, and because many are doing it there must be value in it? Well, there is one born every minute they say, and you can make a lot of money from selling snake oil or success recipes. You clearly will not make a lot of cash offering services that involve telling people inconvenient truths.

Nonetheless, there is nothing like a monumental challenge to get you motivated. Richard and I connected as we are both on a quest to do our bit to shift management practice from pseudo-science, anecdotal evidence or “best practice” to a foundation of sound theory. There is plenty of good stuff out there, both past and present. It is, however, not easy to package it up into a three or five step process that guarantees success.

The reality is that transforming an organisation will be messy, it is unpredictable, we will not have all the answers up front, and it will take a lot of work. It is hard to get people to queue up for that type of show, even more so when they also have to play a part in the performance.

Richard and I have both been labelled as highly cynical and pessimistic but nothing is further from the truth, we’re what Richard calls, frustrated enthusiasts. We care deeply about the state of organisations and how the people in them feel about work and subsequently themselves. Richard’s research clearly shows that organisations stand to learn a lot by embracing the cynics and ironists. They are the ones who care enough not to become part of the walking dead. They are the survivors who fight back.

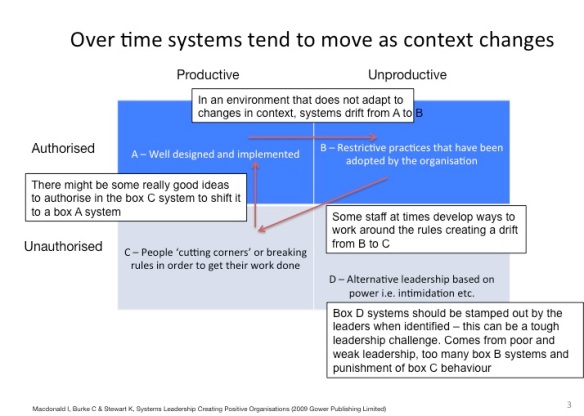

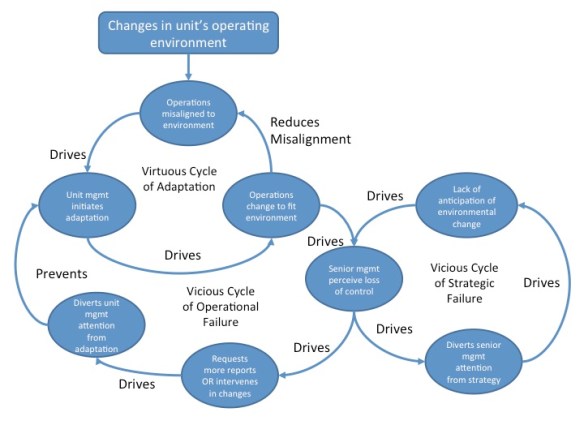

The employee engagement percentage is reportedly at 13% globally. The low engagement levels, however, are self-created, and the cure is not about fixing the people, it’s about working on the environment in which they work. Something we’ve known for a very long time but struggle to put into practice. Instead, we are creating the walking dead in our organisations by the constant dumbing down of work due to rules, policies and other constraints in attempts to standardise and control behaviour.

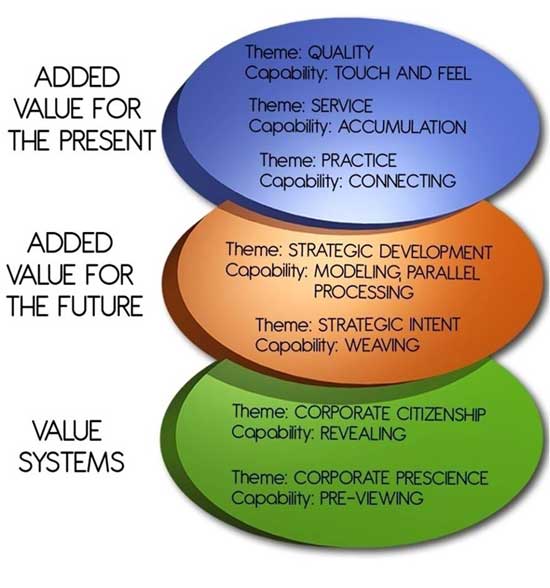

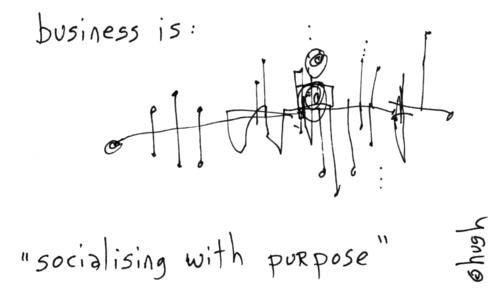

The picture above represents a healthy organisation. Think of an ECG monitor and you get the metaphor. There is an abundance of life; people have the freedom to work out how to go about their work within clear boundaries. The goals or objectives can at times be hard to define or might change along the way, which is why it is not a standard shape. In a complex environment, this is situation normal.

Unfortunately most organisations look more like the image below. Through policies, rules, standardised work practices, ERPs, etc., the organisation has flat lined, creating an army of the walking dead. The end state is a defined shape, to represent an assumption that we always can identify the end and work towards it.

So how do you fight off the walking dead without losing your head during the process and without compromising your morals? How do you re-energise an organisation and bring its people back from the land of the walking dead?

Well, that’s the million-dollar question, and this is the point where we should outline a five-step process for success. Please note that any attempt to successfully fight zombies or the walk ing dead by attacking individual zombies is doomed to fail. The people on your side that fall in the fight will join the other side; you are fighting a losing battle. Finding the source of the problem and dealing with that is the aim. The realisation of what the source is for many organisations is illustrated well in Walt Kelly’s Pogo cartoon.

ing dead by attacking individual zombies is doomed to fail. The people on your side that fall in the fight will join the other side; you are fighting a losing battle. Finding the source of the problem and dealing with that is the aim. The realisation of what the source is for many organisations is illustrated well in Walt Kelly’s Pogo cartoon.

Many leaders will only see one way out, which is to copy what others do or what worked in the past (which rarely makes you a leader in any field). Others find themselves where two roads diverge; do what everyone else does, or something different. Few have the courage to take the road less travelled, but for them, it will make all the difference. Travelling on this path takes not only courage but also stamina and openness to unlearn and learn.

We don’t have a five-step success plan for venturing down the road less travelled. What we do have though are some thoughts and considerations on how you could go about this.

- Identify your cynics and ironists. They will be essential to locate, not only because they sit on a world of knowledge about the many ways in which your organisation trips itself. But they also care enough about the organisation and its people to work with you on changing it. For some, it will be an opportunity to put into action things they have thought about for a long time. This is also an opportunity to map the informal networks of the organisation to get a feel for who is connected to whom and where the key influencers are.

- Understand the current mythologies of your organisation. You need to know what the current beliefs are in the organisation, concerning the behaviours that are seen as positive or negative on the values continua. I’ve written briefly about the values continua previously; you can find it here. Mythologies are not about individual views; it is about the shared mythologies, the shared beliefs that create social cohesion amongst groups in the organisation. Understanding the present reality for people in your organisation is essential as it is from here, and only from here transformation can begin.

- Conduct a Systems & Symbols Audit. You need to lift the covers and look deeper into the fabric of the organisation to identify systems and symbols that reinforce either positive or negative behaviours. The underlying assumption here is that systems drive behaviour, so this provides valuable insights regarding possible intervention points. Questions to consider include:

- To make sure your head stays connected to your neck and to maintain your morals, understand that it is in the social dimension where it is won or lost. The technical elements are usually the easiest aspects and sometimes they are irrelevant on the whole. Good social process is something that will carry you a very long way. People can deal with many things if they feel that they way they are being treated falls on the left hand side of the values continua. If you are leading transformation and don’t live in the future, you are likely to fall short or your intent. Behave as if your organisation had already transformed, live the behaviour you feel represent the new. That requires self-awareness, self-reflection and a certain level of maturity. Of course, you will fail at times but it is important to role model behaviour as people pay more attention to how you behave than what you say, just like your kids.

- Engage the whole organisation in an ongoing conversation about what the future can be and how to make this happen. All the answers for how to create a positive future for your organisations are already contained within it. The challenge is how you allow the creativity and ingenuity of your people to get out and get their ideas into action. Successful change is co-created, not implemented by edict from the top. Take the time to develop a connection with people to understand their needs; the ideas and strategies to meet these needs will flow almost as they had a life of their own once the needs are clear. There is a range of helpful techniques for facilitating large groups sessions, for example, World Café or Open Space Technology where good social process is at the centre of the design.

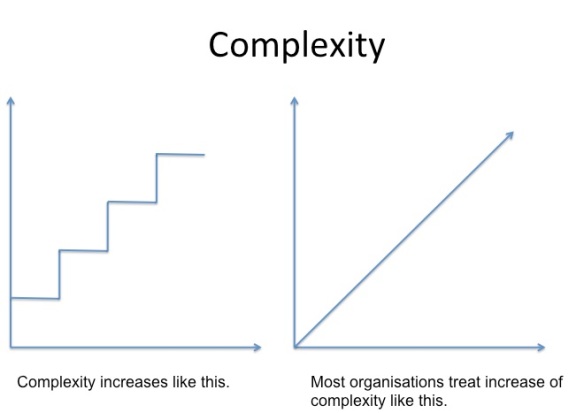

- Acknowledge that some challenges will be in the complex domain and other will be in the complicated domain. In the context of organisations, these are not words to be used interchangeably, even though in everyday life this might be the case. Think carefully about how you might approach a complex challenge differently to a complicated challenge.

An excellent example of the power of social process is David Marquet’s book Turn The Ship Around. David takes control of a Nuclear Submarine and the story is a classic one – take a bunch of people labelled poor performers and turn them around to become the top team. The interesting thing to reflect on is that David achieved this using the same technology as all other similar class submarines, he did not get some special funding to do this so the only area he worked on, and relentlessly so, was on social process. Essentially the story is one about how good social process can be the difference that makes a difference.

I’ve deliberately stayed away from referencing much theory here but rest assured that there are strong theoretical underpinnings to these thoughts and considerations. When people tell me that they don’t have time for theory or their senior executives don’t have time, they just want something practical, I shake my head and sigh. All our actions are informed by theory, i.e. we hold some view about why this action will or will not be useful in this situation. The difference is if the theory that you are applying is useful or not. We would like to help you make better decisions by grounding your thinking and decisions in theories that truly are useful.

I invite you to get in touch if you are willing to explore how we can enrich the life of the people in your organisation.