Managers work of role

Systems Leadership Theory defines the role of a Manager as:

“A person in a role who is accountable for their own work, and the work performance of others over time.”

I think the purpose can be shortened a bit and this statement might be controversial, but if you are in a managerial role then in simple terms, your role is there to:

“Maximise performance to purpose.”

Before the systems thinkers out there start jumping up and down saying,

“What about sub-optimisation?” just hold on to your hats and please read on.

Taking a systems view of work and of organisations means you must understand not only your system of work, you must at a minimum understand the purpose of the system “above” (the system that your area is a sub-system of) because that system provides the context for your system’s existence. This means that clarity of purpose is critical, in fact so critical you will see a recurring theme in many of the models clarifying context and purpose.

This could mean that from the perspective of any single unit or division, it may not operate at maximum capacity as performance has to be viewed in the context of the broader system and sub-optimisation is a big no-no. I will get to this topic when I discuss the “understanding the work” element.

Value adding

An important aspect of a well-functioning organisation is the value-adding function of the different roles. Systems Leadership Theory identifies three main types of managerial roles – Operational, Support, and Service. I think it was John Seddon from Vanguard who said that there are only three roles in an organisation: one that creates value directly to the customer, one that enables that value creation to occur, and one that improves how they both occur. If you are not creating value, enabling it or improving it, then what are you doing?

These two ways of articulating types of work focus on the individual rather than the organisation. To create clarity of the broader focus of a role using different work domains as outlined in Luc Hoebeke’s – Making Work Systems Better is quite helpful for identifying the general theme of the work context. The work domains are – Value adding for the present – Value adding for the future – Value Systems (value adding for humanity).

There are additional functions required for a viable system from a management cybernetics perspective but we’ll get to that when discussing organisations as systems later on.

Master – apprentice

In many organisations the individual with the most experience or best technical skills gets promoted to a managerial role. We can see it in health care where the best surgeon becomes the administrator; in accounting firms and law firms it is almost standard practice to task senior partners with running the organisation, even though their skills in this area might be very limited.

Often the remuneration system is the culprit as the only way to reward individuals is by increasing the number of people reporting to them and by moving them higher up in the organisation. Even though this means doing less of the technical work they are highly skilled in (and often enjoy more than the additional administrative work). They would probably add more value being in a specialist role focusing on their technical skill and perhaps developing the skills of others.

The e-myth is a great book discussing the idea that just because you are technically good at something does not mean you are good at running a business that provides that technical skill.

For some types of organisations, roles, skills this practice still serves a valuable purpose – to pass on the technical skills that you will only master through experience. So this is not to say that the practice is out-dated, just questioning its usefulness when it comes to appointing Managers based on technical skills or seniority. In fact praxis (theory informed practice) is invaluable even for knowledge workers as a great way to develop true understanding and capability.

In today’s environment with a large proportion of organisations filled with knowledge workers the Manger is unlikely to have higher level of technical skills than the person reporting to them.

“At the beginning of the twentieth century, it has been estimated that 95 % of workers could not do their job as well as their immediate boss. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, it is estimated that this statistic has pretty much reversed, so that 95% of workers can do their job better than their boss.” – The Fractal Organization

So if you are technically more competent than I am in your area, then how do I add value to your work? I think it is funny how some people have a view that their Manager ought to know more about the technical side of the work than the people working for them. The view does not stack up logically as the CEO by that logic must be the master of everything in the organisation.

This is exactly why we have organisations – because there is too much for any one person to do we need more people with a wide range of skills and capabilities. The question is how to get the best out of all those diverse skills and capabilities.

Levels of work

In many organisations the organisational chart is used to describe the organisation, even though its use for that purpose is desperately limited. I don’t think the organisational chart was ever intended to explain how the work flows, it is just one way of outlining reporting relationships and possibly a helpful way of knowing who’s who in the Zoo.

The organisational chart can easily be used to manipulate the system of organisation into power plays based on role vested authority and drive all sorts of unproductive behaviours but it does not have to be that way. I think the traditional organisational chart has to be used in conjunction with some other ways of understanding the organisation.

Before I continue to how Managers add value I want to make a short comment on role-vested authority. As a Manager it is critical that you understand that leadership is not something that comes with a role, it is expected, but you have to earn the right to lead people and without personally earned authority you will never be successful as a leader.

According to Elliot Jaques there is natural hierarchy of capability that should be replicated in the managerial hierarchy of organisations for best performance – hence the name, Requisite Organisation. I have in an earlier post linked to a good paper that goes into Levels of Work in greater detail. It might be worth pointing out that a theory of discontinuous distribution of capability should not be interpreted as elitist in any way. There is nothing inherently better or worst being at any stage of adult development or having higher or lower mental processing ability – it is just a question of best match for the challenge an individual is to undertake.

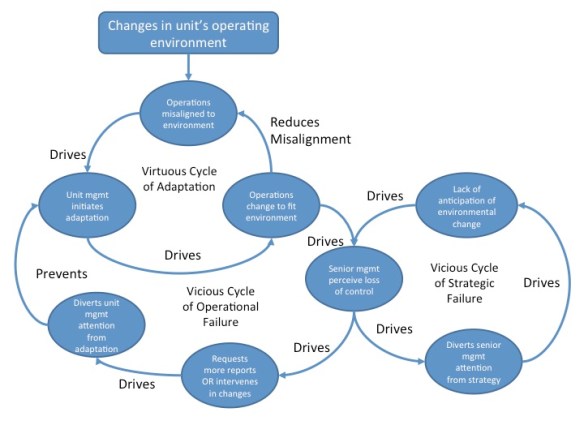

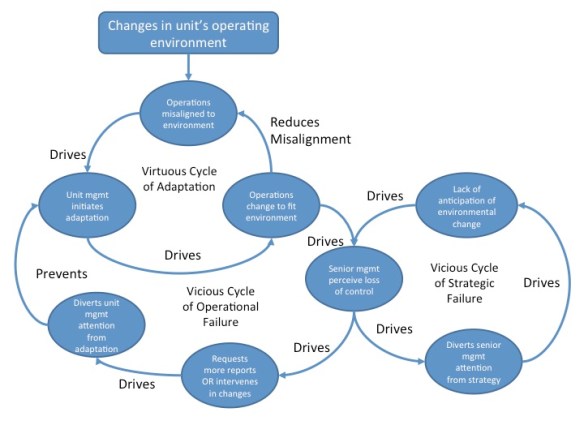

If the organisation does not have a requisite structure there will potentially be some recurring issues. When there are too many layers in organisations, clarity between roles can become difficult and it will often lead to micro managing.

Micromanaging is often seen as a personality issue with control-freaks but as Patrick Hoverstadt points out in his book “The Fractal Organization” it is more likely the design of the system that is driving “normal” people to behave in this way.

The solution to the Control Dilemma is to design and implement a better system of monitoring which might mean better measures for understanding system performance, improved role clarity, and better task assignments.

When working with organisations and trying work out where there might be too many levels some a quick insight is gained by asking the question: who is your real boss?

The answer people give, usually refers to the person that they feel add real value to their role rather than who is on the official organisational chart. More often than not this will be an individual with a higher level of capability.

The value managers provide is providing clarity about roles and operating context, and most importantly by removing barriers that stand in the way of better ways of doing the work.

There are three fundamental questions about work that all employees need answered and your job as a Manager is to ensure that your staff have answers to them:

1. What is expected of me in my role?

2. How am I performing in this role?

3. What does my future look like (in this organisations)?

Dave Snowden from Cognitive Edge suggests that continuous removal of small barriers is good ways for leaders to earn the authority to lead. Snowden makes the point that this practice will lead to positive stories which will get a life of their own and spreads across the organisation (The Use of Narrative), a far superior way of influencing culture compared with just talking about change. This is very aligned with what Systems Leadership Theory calls mythologies – stories that represent positive or negative value of organisational behaviour. Understanding what the current mythologies are is extremely important for change initiative. I’ll cover mythologies in greater detail in an upcoming post.

Alternatives to hierarchy

Even though I am discussing how to make organisations with a hierarchical structure a better place to work, I am also exploring alternative ways of structuring an organisation. I am deeply fascinated by the concepts of Sociacracy and Holacracy as alternative ways to structure and run organisations. Both concepts have strong links to Management Cybernetics, which is another theory that I work with.

I do, however, have some deeply held mental models around levels of mental processing ability and stages of adult development that neither alternative seems to discuss.

The only references to adult development I’ve come across to date is paper on Holacracy that mentioned a common misunderstanding was to assume that a higher circle required later stages of adult development. The reason Holacracy rejects this was the potential for is to lead to abuse of power. The problem with that assertion is that later stages of adult development are characterised by low ego and highly developed sense of community and social fairness, not quite the characteristics of people who are power-hungry.

For more on adult development theories please have a look at David Rooke and Bill Torbert’s Leadership Development Framework supported by Susanne Cook-Greuter’s article “Making the case for a developmental perspective” or Robert Kegan’s Constructive-Developmental Theory used by Jennifer Garvey-Berger in her great book “Changing on the job”

In the next post I intend to discuss work as a social process, I will outline a model for participative decision-making and a model for task assignment that helps provide clarity around expectations and limits of discretion.